The man gently lifted his injured cockerel from the dirt of the arena, its body still and its head hanging from his thick hands. Around the arena, in sloping banks of wooden bleachers, other men stood shouting out bets and passing money to the bookmaker. They clutched bottles of beer as they chatted and bellowed and laughed.

The man cradled his stricken fighter as he walked up through the narrow aisle to the back of the small arena where he disappeared into the dark. It was his last fight of the day, and mine. I no longer had the stomach to watch these fighting cocks try to strip each other’s blood to the sand.

The Merchant

A couple of hours earlier, a merchant stood behind a small wooden table laying out his wares on the flat ground above the cockpit. Above him a high corrugated metal roof covered the entire arena and its outskirts, casting a cool dark shade upon the dirt floor. The late-afternoon sun beat down on the ground outside the shade of the coliseo de gallos, a bright fringe of raw Amazonian heat.

A few locals had gathered, but there was still half an hour until the fighting began. Women were cooking strips of cecina and pieces of chicken on their grills, the smoke drifting in the still air, while children scurried around playing tag and kicking up dust.

The merchant unfurled a series of red leather cases. Inside were neat arrays of cockfighting spurs. Some glinted in the half-light; they were made of metal. Others were dull and made of plastic. The most expensive were made of fishbone. I asked the merchant how much they cost. “These are the best,” he said in his lilting jungle Spanish, pointing to the fishbone spurs, “Four hundred soles.” That’s serious money, I thought. More than $120 for a couple of foot-spears designed for aggressive chickens.

But this was my introduction to cockfighting in Peru, and I had no idea how much money was involved, even at a small neighborhood coliseo like this one in the high-jungle city of Tarapoto.

The Careador

The careadores — the owners, trainers and handlers of the fighting cocks — began to arrive as the sun slowly descended toward the jungle-coated hills of the horizon. They carried their cocks in neat carrying cases, especially designed for the purpose. They took their birds to the weighing station, where each cock was gently hung from a scale and weighed quite carefully. Like a professional boxing bout, the matchups would be determined by weight.

I’d seen fighting cocks like these tied up all across town. On soccer fields, on top of bare brick walls, down on flat banks by the river where the women scrub clothes on the smooth rocks. The cocks would be tied by one leg to a small stake in the ground, presumably so they could get out of their cages for a while. A loose gallo de pelea, a trained fighting cock, will typically go on the offensive at any opportunity, so they are not left to roam freely.

In most cases, a proven or promising fighting cock is well cared for. Not like a pet, but like a champion, like a tiny feathered boxer who can make a pretty penny for its owner. And the training is not cheap. A careador will spend thousands of soles for each of his cocks, on medicine, food, care and training. And some won’t last long, making the investment a risky one.

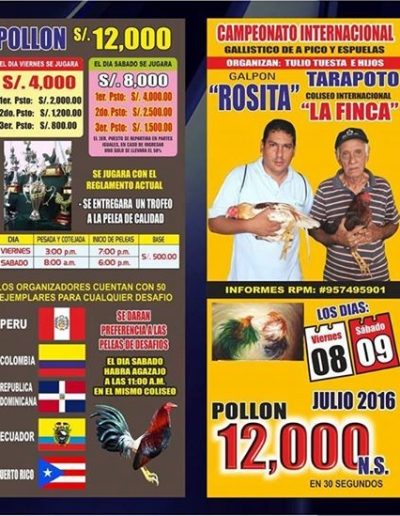

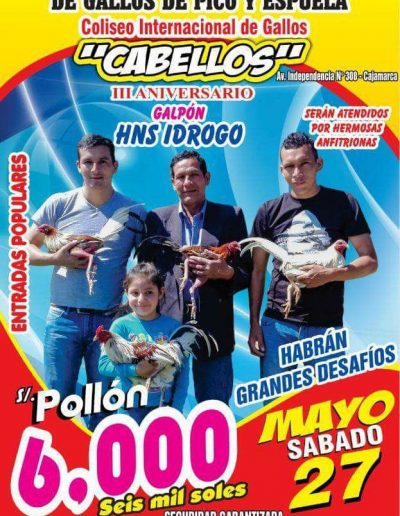

The potential rewards, however, offset the risk, at least in the minds of the determined careadores. They eye the pollón, a prize awarded to any trainer whose cock defeats its opponent in a certain amount of time, usually between 30 and 45 seconds. That’s a rapid victory considering many fights have a total duration of about eight minutes.

The prize for the pollón can be anywhere between S/ 1,000 and S/ 30,000 ($300 to $9,000), depending on the tournament. Throw in the other prizes for simply winning fights, and the overall pot can be impressive. The monthly minimum wage in Peru, for scale, is S/ 850, or about $260.

The Spectator

With the fighters weighed and the crowds assembled, all eyes shifted to the sunken cockpit at the heart of the coliseo de gallos. The sand at its center was freshly raked in a circular pattern.

It was a full house; the energy was growing as the sun set, casting the world outside into humid darkness. But the strip lighting above the arena poured light down on to the brown sand, attracting circling moths and other insects into the world of the coliseum.

I sat in the second row. I’d decided that if I was going to watch something that instinctively repelled me, I’d do so as close to the action as possible. Through the packed rows of ascending seats all around me, three narrow stairways ran down from the rear of the coliseum. Each ultimately descended to a small opening onto the arena sand: Two thigh-high white doors for the rival careadores, and one for the juez, or judge. Once the judge was in position, the two trainers walked down, each carrying his fighting cock, both in the lowest weight category.

The bets immediately started to fly around, shouted to the front of the arena where a man stood with one hand full of banknotes and a notebook in the other.

Despite the bets, the beer and the soon-to-start blood sport, it was not a seedy event at all. No gangsters, no clandestine exchanges, no watchmen at the fringes looking out for the police or animal welfare agents. All legal, all above board, no police or protesters. In fact, it was one of the more organized events I’d seen in Peru, with people from all social classes. Children still scurried around at the back, seemingly uninterested in the cockfights, occasionally coming down into the crowd to ask dad for some money for chicha morada or a cooling raspadilla.

The two careadores knelt on the sand at opposite sides of the arena, their hands placed firmly on their respective fighters. The men raised their birds and shook them at each other, agitating the cocks and stirring their aggression. Then they pushed the straining birds to the ground. A buzzer sounded and the careadores released the fighters before leaping over the low arena wall into the crowd. In an instant, the two cocks were at each other, a frenzied confrontation of audible pecks and the strange sound of spur and beak on feather, like the rapid rasping of wood on wood.

No pollón occurred between these two lightweights. The fight dragged on and the cocks tired, circling frequently with occasional flurries into the attack. It went the full distance and, as far as I could tell, the judge declared a stalemate, a tie.

I sat relieved, glad that neither bird had died or been maimed. Both looked fairly healthy when the fight ended and their trainers carried them away.

A second fight followed, much like the first. Lightweights, agile but seemingly lacking any quick killer blow. Feathers were plucked and the sand was scuffed and scattered, but the birds were carried away, again unscathed.

The third fight was a different experience. Two larger cocks — perhaps of the heaviest weight — were brought down by their careadores. They were impressive creatures, proud and sturdy, with red and black feathers, sleek and shiny.

The fight was brutal. The impacts now rang out with ripping and wet cleaving sounds, and the cocks frequently became interlocked. Occasionally one would fall flat, obviously stunned, until its owner jumped into the arena to prop it back up and send it wading into the fight like a wind-up toy. They clashed and entwined, split and tore feathers, and more and more it seemed like this one was to the death.

It was a sick sight, far more so than the previous two bouts. But the crowd was more energized than before, and the spectator numbers had swelled. Cries of fresh wagers flew through the air: “Fifty soles on El Negro!” “Thirty soles on Pelo Rojo!”

The red-feathered fighting cock fell in a heap following a vicious spur strike from its rival. Limp, it lay in the sand alongside a few spatters of blood. It was done, it was over, and his owner leaped into the arena once again, this time visibly concerned. He lifted his fighter in two hands, its head hanging, and left the arena while the bookmaker tried to manage the bets of the boisterous crowd.

For me, I’d seen enough. The warm night was still early and far from over, with perhaps 10 or more fights to go, and I had no intention of watching another.

On my way out, I passed the merchant at the back of the arena. He smiled and asked me what I thought of the cockfighting. I told him it wasn’t my kind of thing. I asked him if he saw what happened to the cock that lost the last fight. “It will be OK,” he said. “It won’t fight again, but they’ll keep it for breeding.” He smiled again.

I’m fairly sure he was lying.

All photos by Tony Dunnell.

How and Where to Watch Cockfighting in Peru

If you want to watch cockfighting in Peru, ask around for the nearest coliseo de gallos (cockfighting arena, or “coliseum”). Most towns and cities have at least one. As mentioned above, it’s not a seedy event. Unlike in countries like the UK, the USA and Australia, cockfighting is completely legal in Peru. The crowd is usually mixed and unthreatening, although you’ll probably come across a few drunk men later in the day.

Cockfighting events in Peru are normally advertised with flyers and posters like the ones shown below.

Have you watched cockfighting in Peru? What was the experience like for you? Share your thoughts in the comments section below. Thanks!

Share This

Thanks for commenting! If your comment requires an answer, I'll try to reply as soon as possible. In the meantime, please share this post with your friends.